In mid-2012, he turned it on.

“Son of a gun,” he recalls. “I’m getting a signal.”

Soon he got up obsessed with making those pingbecs pour into his antenna. At the beginning of 2013, he came out live with a website – then www.satwatch.org– where he uploaded data.

At one point, he had observations of 150 satellites. It refines their signals, turning the received frequencies into notes that human ears can hear. He loved to catch the secret military space shuttle that sounded like video game monster in agony. He likes the International Space Station, aurally similar to A UFO throws a bomb almost to the ground, and then sends it back to the tractor just in time. He liked the secret shuttle and the Chinese space station. And then there was the North Korean satellite Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2, a kind of shy bird.

Colette seems to like to see things that aren’t necessary. The radio waves from space objects are, in a sense, the great equalizer: What comes down from the sky belongs to anyone who can find it, and to anyone who has hangers and a computer. But one day Koleta’s collection of thoughts stopped growing.

On September 1, 2013, he was sitting waiting for the ISS. But when the time came, his plots simply twisted the statics. “Hey, where’s the space station?” he thought. Then, when nothing else appeared, he thought, “Hey, where’s everything?”

“It happened,” he said in his webcast Space Gab. “It finally happened.” The Air Force had activated the space fence, to save millions after sequestration. The agency is building a next-generation fence, scheduled for initial inclusion in 2018. But it will transmit at too high a tuning frequency like Coletta’s.

“It was the worst day,” he said.

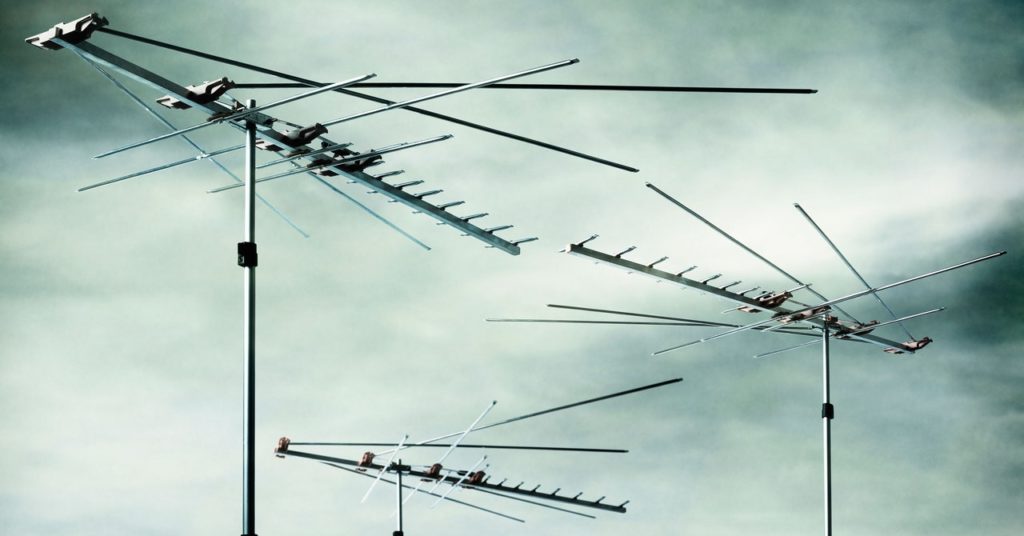

But Colette didn’t give up your hobby. He made a receiving antenna from rabbit ears and later installed his current set of four antennas. With them, he receives live broadcasts from satellites, not just their reflections. Together, its antenna view covers almost the entire sky above his house, and a North Korean satellite, Kwangmyŏngsŏng-4, is about to appear.

It seems to be an Earth observation satellite that can broadcast propaganda / patriotic songs. Colette’s antenna has to be to hear this hypothetical music – and he’s trying and trying to capture the signals of the 2016 satellite. He’s trying again today. “Wouldn’t it be cool if he showed up?” He says. But NOTHING.

Oh, good. One of the things he likes the most these days is looking for satellites that no one is officially interested in anymore. They are the ghosts of the space age, technically just space junk. But the satellite operator’s garbage is the satellite hunter’s treasure.

On the board to the left of Koleta is a list of antiques, their frequencies and years of launch, scratched next to them. NOAA-9 – “perhaps the most musical satellite up there”, which sounds like a drunken uncle whistling at you – is one of his favorites.

About a third of the column is a seat called the LES-1, which Lincoln Labs abandoned until 1967 and which the iPad says will fly soon. The LES-1 was silent for decades, but in 2013 another amateur discovered that it surrenders when its solar panels encounter sunlight. Koleta also saw him and went back and forth, fascinated by her resilience. But not long ago it disappeared.

He prepares the computer interface anyway, with hope. Maybe today is the day. We are waiting.

But LES-1 passes silently. He can’t talk to Colette, and Colette has him never I could talk to him. Almost everything is like this: a one-way conversation, from space to setting it up.

It goes from a disappointing live screen to an old July recording. These are astronauts, he says, who speak on Earth.

At first there are only static. Then the voice disappears in and out. Colored ribbons accompany each half-sentence: “Too great to imagine … help humanity explore and grow.”

“You can hear them on TV all the time,” says Koleta. But it’s different when you can hear them on TV antennas you tweaked to provide a different kind of entertainment.